Current Projects

Camera Consciousness: The Aesthetic and Prosthetic Legacy of World War I

This project considers the nervous system, the camera, and the prosthesis during the social and technological upheavals of World War I and its immediate aftermath in Western Europe and the United States. The focus remains roughly the period of 1914 to 1933, when the speed, scale and intensity of warfare surpassed human phenomena, necessitating radical revisions to body/machine interfaces, medical and social institutions, military training, and labor practices. Such traumas and mediations, I argue, continue to resonate in contemporary warfare.

The “camera consciousness” evoked throughout the book is not limited to the apparatus specifically—for example, to a cinema spectator’s adoption of the movie camera’s point of view—but rather is proposed as a way to understand modes through which still and moving images began to frame and project events and bodies in order to contend with the traumas of the Great War. The camera’s association with rational detachment was utilized to instill a sense of order in a period of grave instability. As such, it is the foundation of contemporary militarized culture and technology. It also reveals the atrocities and alienation perpetuated in the name of such order. Above all, camera consciousness is addressed as an aesthetic and episteme bound to the growing awareness that the modern subject is already a system of parts and part of a system that is continually reconfigured through technologies as small as the artificial limb and as large as the city or battlefield.

Human-engineered catastrophes, emerging in the industrial revolution and culminating in the grand disaster of World War I, conditioned modern consciousness. Thus, I addresses the shocks of the railway accident, the dissolution of traditional vision and identity in the face of nineteenth-century urban masses, and the alienating mechanization of the body consumed in new automatized technologies. Exposed to the peril of nervous fragmentation, urban subjects responded to visual excitement through the intellectualized perception of the camera, which seemed to screen and master these shocking temporalities. The apparatus could frame and repeat the traumatic for therapeutic replay; aid in screening for potential catastrophes; record the somatic effects of shock (nervous tics, spasms, etc.); increase or restore sensorimotor capacities often pushed to the point of breakdown at the overwhelming demands of combat; and through the aesthetic of disciplined mass assemblages, in which the masses appear as a singular body, soothe the anxieties of industrialization and mobilization. As such, it embodies the analytical eye and detached stance deemed necessary in modernity and became central to the trope of the technologized warrior. The “psychotechnical” tests, for example, conducted with the camera during and after World War I were integral to the optimization of human-machine systems such as the prosthetic limb, the antiaircraft gun, and increasingly complex feedback technology that are the foundation of contemporary computers, videogames, and combat interfaces. The camera also rendered visible the tenuous construct of individual autonomous identity. Photomontage presented strange mechanical and fragmented figurations; efficiency tests of workers and clinical studies of shell-shock patients broke down the body into distinct units to be modulated; and images of amputees or the disfigured were systematically documented to emphasize the subject’s malleability—and thus productivity—with the aid of surgery, prostheses, and training.

The therapeutic or shielding function of the camera, however, threatens to limit human experience to surface phenomena of photographic images and a series of present moments. The limited time for the processing of events into contemplative sequences appears to decay individual and collective memory, thwart traditional modes of self-representation and social integration, and thus risks severing the citizen from history. Walter Benjamin chronicles this loss as the decline of the “storytelling function,” embodied in the peculiar silence of veterans returning from the war. The surface phenomena of the photograph, devoid of history and sequential narrative, has intensified and expanded into an infinite web of depthless vision in digital media. Combat videogames, for example, privilege spectacle, Erlebnis, and the sensorimotor challenges of the interface over the Erfahrung of historical context and critique. These modalities of the image that deliver a thrilling barrage of shock moments to be mastered thus tend to interpellate the spectator/gamer not as a citizen, but as a soldier. After all, it is the soldier’s prerogative to learn how we fight and the citizen’s duty to question why we fight.

The analogies or parallels to current war and media are not always asserted throughout much of the book, although many of the artifacts and discourses evoke similar issues today. The concluding case studies on combat videogames, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder therapy simulations, and the trope of the disabled veteran pull forth observations drawn throughout the chapters, revealing that so-called new media has a longer history than commonly discussed. Mobilizing visual studies as a discipline that utilizes art history, media studies, critical theory, disability studies, psychoanalysis, and cybernetics, the emphasis nevertheless returns to the visual, both in terms of the ways in which spaces and bodies are constructed and presented, and in terms of the individual’s reactions to perceptual and cognitive ungrounding brought on, above all, by the shocking intensity of modern war. The objects of study, ranging from war literature; artistic, scientific, and journalistic photography and film; Dada montage, drawings, and paintings; Brechtian theater; and finally contemporary combat videogames and interfaces are addressed in relation to the new phenomena and epistemologies of photographic and cinematographic technology to emerge in the milieu of industrial war and the precarious social order of interwar Europe and the US.

The image of the wounded veteran, as the bearer of psychic and somatic trauma, is an index of technological and cultural transformation. Thus, my argument builds upon disability studies and theories of “the prosthetic” through the figure of the soldier, typically young, male, generally able, and an early adopter of new technology—for even this presumably dominant and masterful figure reached a breaking point. Such crises of masculinity, embodied in this soldier, were central to the discourses and representations of modernity. With the perceived loss of autonomous individuality and a meaningfully ordered interior life, many survivors turned to new machines and media that promised to armor the modern subject for the dawning age of total war. Ernst Jünger, the primary subject of chapter two, presents war as a cosmic spectacle in which the individual is consumed in the intoxicating speed and intensity of industrial battle. A technological sublime par excellence, the war lay to waste the bourgeois subject and the values of comfort, security, and autonomy. Overwhelmed by a plethora of stimuli, traditional corporeal and sensorial boundaries were disordered. “Prosthetics” such as the camera that enabled the compiling of perspectives and the freezing of motion emerged alongside its material counterparts that underscored the partiality of the body as well as its connection to larger social and mechanical systems.

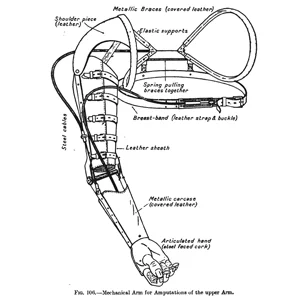

Identities and corporal boundaries are fluid affairs, and the understanding of what it means to be a fully functioning human is under constant revision. The increasing tempo of personal computers and handheld devices, for example, places new demands on perception and cognition, and changes the parameters of “normal” bodies and capacities. And the camera remains essential in establishing and recording relations between bodies and environments, in determining normal, ideal, or problematic capacities in a given milieu. While the prosthetic limb is by no means a modern artifact, the emphasis on its machinic function over mimetic form was brought to the forefront during the First World War, an era in which the production of new technologies was surpassed only by the destruction of bodies. With the introduction of new mechanical prostheses, artificial limbs began to change from a purely cosmetic replacement to devices that would enable the veteran’s return to productive life. The technologies developed to replace the missing limbs of soldiers and workers were not only important in restoring the lost functions of an individual, however. They also promised to suture the social crises the war produced; to restore the gender role of the independent, capable, and commanding male; and to reassure a wary public of technology’s contribution to the social good. This is not to say that such prosthetics refigured the subject whole—for, as this project demonstrates, new limbs, and other “extensions” such as weapon systems and workstations, promised to add new dimensions to the partial and multiplicitous body.

The major shift in the design of prosthetic technology during and after the war—from the imitation of natural limbs to the function of mechanical tools—was paralleled by developments in the aesthetics of modern photography that would affirm the specificity of the apparatus. This book sets out to ground this development in the social and material conditions of the war and the soldier. It also unpacks the implications of this apparent shift from an organic/imitative to a mechanical/functional paradigm, expanding upon this to include other parallel and related developments, such as the shift from the constructs of a “whole” autonomous individual to that of subject as a “system” and process through which experiences and events unfold. The first two chapters address this primarily through the camera and its modes of perception, while chapter four presents specific mechanical prosthesis—primarily through Jules Amar; and chapter three considers the overlapping “prosthetic aesthetic,” or alternately, an aesthetic of dismemberment through the Berlin Dada, Surrealism, and Brechtian theater.

In contrast to the experience of disability among civilians, the veteran’s experience of post-disability social integration is collective, shared with other military personnel, and reflects the state. A trope and reality in his or her own right, the wounded soldier stands as a signifier of institutional, national, and technological tensions—for such scars are continually imbued with meaning. Such veterans are both revealed and concealed as embodiments of national reconstruction and social responsibility, of medical technology’s capabilities, and of the (typically) masculine spirit in adversity. Focusing on the image and rhetoric of the disabled veteran, I negotiate between the trope of the prosthetic as a means of understanding technological extension and of the prosthetic’s visual presence and embodied “absence” as incorporated into the body’s schema. The disabled veteran, marked under the rubric of duty and sacrifice, carries the additional weight of honor or shame, pity or admiration.

Central to the prosthesis as a material reality, as a lived and incorporated object, is the disabled body it serves. Throughout the book, the images and rhetorics of disability are addressed through two frames: the incontestable and visually striking deformed or amputated veteran, and the generalized disability of non-optimal capabilities or efficiency in which all subjects of modernity are to a degree “afflicted” and require technological intervention. It is in this way that the prosthetic appears as both a specific manifestation as well as a system of discipline. Physiology, rationalization, and scientific management, discussed in chapter four, attempted to overcome these perceived shortcomings; at the same time, however, they narrow the parameters of what constitutes a normal, healthy, or complete body.

While traumatic wounds such as the loss of a limb are incontrovertible evidence of diminished capacity, nervous disorders are characteristically difficult to visualize and quantify. The problems of disability’s visualization is addressed throughout chapter one, first as nineteenth-century neurology attempted to comprehend the peculiar and vague conditions of enervation or nervousness, and later under the pressures of the World War I clinic as a means of screening perceived malingerers as well as a tool in establishing the authority of the doctor in disciplining—if not curing—the war neurotic. Photographs of amputees and facial disfigurement were integral to the archive of veteran clinics which documented new surgical processes and displayed the possibilities of national reconstruction through, among other things, the process of returning men to work and regaining social independence. But many victims of the war, particularly those who had literally and figuratively lost their face, were often shamefully hidden away. Chapter three examines such problematic bodies as a motif of the European avant-garde, primarily through Otto Dix and Bertolt Brecht, as aesthetic and social rejections of conventional constructs of subjects and state. These images of somatic and psychic fragmentation, I argue, resonated with the public at large who generally felt besieged and reduced by the demands of modernity. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, addressed in chapter four with other motion study experts, attempted to rhetorically bridge the plight of the disabled veteran with the overarching drive for efficiency, for everyone is, under modern rationalization, in some way a “cripple.” Enabling the perception of the body’s micromotions—in terms of both pathological tics or minor but inefficient eccentricities—the camera discovers the “optical unconscious,” to use Benjamin’s term, just as the instinctual unconscious was discovered through psychoanalysis. The enriched field of perception brought on by film supports Freudian theory, and Freud’s conception of the psychic shielding of shock is addressed in the first chapter, as it developed in response to war trauma as well as the photographic apparatus.

The perceptual and cognitive parallels between photographic representation and the experience of mobilization led to theorizations of modern consciousness as an imaging machine. As industrial war and mechanical reproduction dissolved the self-contained individual, the camera promised to assemble the militarized subject. Jünger uses the camera as a metaphor for a hardening required to contend with the conditions of modernity; it is integral to the objectification of life and thus to the mastering of pain which inevitably increased with technology. He constructs a theory of a new type of human who looks at the world with the unflinching precision of the camera, and who remains shielded within the masklike image photography affords. Even as the camera itself is conceived as a prosthetic sense organ, its reframing of bodies, machines, cities, and armies enables the convergence of technology upon and around the human.

While contemporary digital networks and complex feedback systems further problematize the construct of an autonomous and contained self, the assertion of the ego persists. The first two chapters in particular address the traumas of this perceived dissolution and consider the strategies—such as Jünger’s technological fetishization—to assert a gestalt, however precarious or contradictory. But whereas psychoanalysis (discussed in the first chapter) concerns itself with boundary questions and narrative constructs of the self, the systems theories emerging after World War I, and developing into cybernetics after the World War II, see such boundary questions as nonsense; boundaries are always blurred in human-machine interfaces. At the risk of oversimplification, psychoanalysis in general continued to address the construct of the contained ego—fighting off and shielding itself from traumatic external forces—while cybernetics turned its back on the nineteenth century and looked to establish new consciousnesses between bodies and objects. Jünger appears to occupy the interval between psychoanalysis and cybernetics, between ego and machine consciousness, both historically and rhetorically. Thus, he is discussed in chapter two as a transitional figure who embodies these tensions.

Finally, the book historicizes the technological and social conditions of the contemporary “war on terror” primarily through the figure of the warrior. This is addressed most explicitly through Jünger’s understanding of a new warrior class, enabled—and indeed necessitated—through the speed, perceptual acuity, and destructive capacities of modern weaponry. Jünger calls for both elite squad-sized units and the population at large to adopt a combative sharpness. Warriors and workers alike are conditioned through lifelong technological training and are thus psychologically fortified against shock.

The twentieth century witnessed a transition from the soldier to the warrior. The term “soldier,” conventionally designates those enlisted in the infantry, assembled in massive units, performing a limited and specified task, and as such implies the loss of individual autonomy, presumably submitting to the state. The rigid formation of brightly clad troops of the nineteenth century, for example, was assembled to display an intimidating singular body and will of a mass. While the camera continued to apprehend such spectacles of state power throughout much of the twentieth century, modern warfare necessitated dispersion, invisibility, and adaptability. The previously distinct image of the soldier vis-à-vis the citizen was the result of centralized power and media, with clear demarcations of the battlefield and home front. The warrior (along with camera- and computer-enabled weapons), on the other hand, indicates a fluidity of boundaries, between nations, between public and private, between home and the “front lines,” between the fighter and the civilian, and between waging war and keeping peace. The contemporary warrior fighting in Iraq or Afghanistan is all but invisible to the general public. The demographic of those who serve narrows; military bases recede from population centers; for the few news organizations covering the conflicts, the fighting is often obscure. Through combat videogames and simulations, however, the home front can presumably experience the tactics and strategies of warfare—and while the public embodies the warrior through the simulation, images of real wounded warriors emerge as embodiments of new technology.

The Aesthetics of Dismemberment: Discontinuity in Dada Montage

“The Aesthetics of Dismemberment” considers the motifs and aesthetics of shock and disfigurement in the works of George Grosz, Otto Dix, and the Berlin Dada, through the contexts of photomontage and the wartime clinic. The tics, spasms, dismemberments, and dissociations of such patients were suitably embodied in the emerging modes of photo- and cinema-montage in which cutting and rearranging are defining formal principles. Likewise, the comic-tragic figuration of the “cripple” came to resonate with an urban populace beset with the shocking demands of industry and mobilization—a populace all thought to suffer from some form of deformation or inadequacy. Dix, an artist initially ambiguous towards the primal force of combat and later a cynical visual chronicler of the disfigured veteran, emphasizes the grotesque malleability of the technologically reconfigured subject. The subject in Dada is often a body in pain, a de- and re-configured assemblage of limbs and organs, yet unlike Ernst Jünger’s Arbeiter—a hardened, militarized worker conditioned by the cool camera eye that favors a detached perspective towards dangers that characterize modernity—these subjects lack the mythic and heroic stance that enfolds them back into an ordered gestalt. While the mass ornament may be a fascist compensation for an individual lack, as well as a mode of libidinal investment in authority, the body as/of/in parts that is often initiated through avant-garde photo and film montage destabilizes both conventional signifying practices as well as the euphoric fascist spectacle. In other words, through the technique of montage, Berlin Dada simulates the physical and psychological symptoms of shock—blindness, stuttering, tics, rhythmical screaming—the literal and figurative effect of disjuncture, of “going to pieces.” Photomontage, which brings forward jarring and ironic visual juxtapositions, is part of a broader aesthetics of dismemberment—breaking apart the image, and the image and concept of the body as such, as a radical critique of unity, function, and signification. If artificial limbs, reconstructive surgery, and the prosthetics of reproductive and electronic media covered over wartime defeat and emasculation, montages of dismemberment made a spectacle of such lack and disjuncture in order to critique and render absurd alienating technology and imperatives of order and productivity that ultimately engendered mechanical slaughter. Thus, the interwar avant-garde attempted to redeem such catastrophes through a mobilization of images indicating a society gone awry.